So lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about this guy:

That probably doesn’t come as much of a surprise to anybody, given the amount of time I spend thinking about Batman in general, but since seeing The Dark Knight, I’ve been trying to figure out why the Joker has become the kind of character that he is.

Looking at the character today, it’s obvious that he’s not only Batman’s arch-nemesis, but that more than any other villain, he’s evolved alongside his opposite number to become something more. In a review of Dark Knight, Ken pointed out that comics–especially DC–are built around archetypes. Superman, for instance, isn’t just a good man with super-powers, he’s a symbol of everything that’s good and selfless with a face and a logo on his chest, and as much as Batman’s come to symbolize the relentless, single-minded pursuit of justice, the Joker’s done the same, becoming chaos itself. As Ken says, he doesn’t believe in chaos, he is chaos. He’s less a criminal and more a force of nature.

The question I’ve been mulling over, then, is why it’s the Joker and not someone else.

I don’t think I’m really advancing an unpopular opinion when I say that Batman has the best villains in comics, but even among a crowd that strong, the Joker stands out. The best villains, after all, are the ones that bring out the contrasts within the hero himself, and that’s something Batman has to spare. The Scarecrow, for instance, does to civilians what Batman does to the superstitious, cowardly lot of criminals. Two-Face has the same split-personality as Batman and Bruce Wayne, but with a mask that he can’t take off. Even Ra’s al-Ghul, who was introduced to give Batman a classic pulp-style villain that would allow for world travel and set pieces, is a powerful, obsessive intellectual prone to uncontrollable rages who has set himself outside the law and devoted his life to wiping out what he sees as evil at any cost, to the point where he seeks out a man with the same sort of drive to carry on his life’s work. But even those characters fall short of the gold standard: Scarecrow’s archenemy may be Batman, but Batman’s archenemy is the Joker.

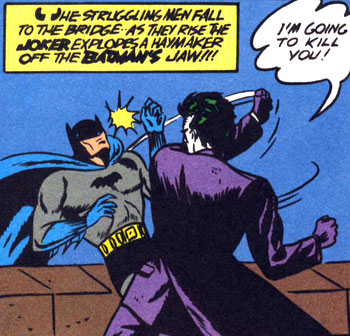

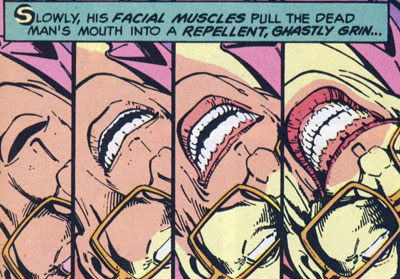

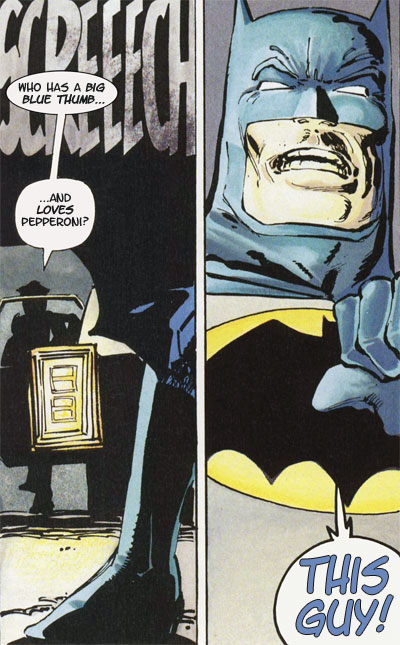

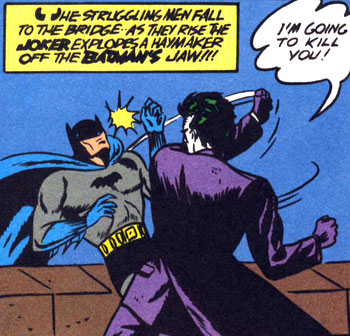

At its heart, you can trace it to the fact that the Joker takes what is literally the opposite route: From his first appearance in 1940, he’s everything Batman’s not in every way but one. Whereas that Batman of the 1940s is a dour, grim avenger in black and grey who works in secret and things like “a fitting end for his kind” when he “accidentally” kicks a dude into a vat of chemicals, the Joker’s loud and garish enough to broadcast his intentions over the airwaves, and while Golden Age Batman was a lot more prone to witty fight banter, the Joker’s alarmingly direct:

in 1940, he’s everything Batman’s not in every way but one. Whereas that Batman of the 1940s is a dour, grim avenger in black and grey who works in secret and things like “a fitting end for his kind” when he “accidentally” kicks a dude into a vat of chemicals, the Joker’s loud and garish enough to broadcast his intentions over the airwaves, and while Golden Age Batman was a lot more prone to witty fight banter, the Joker’s alarmingly direct:

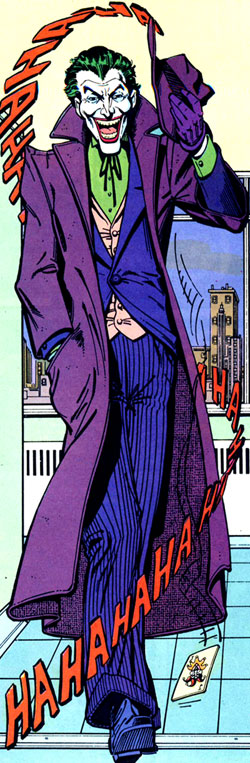

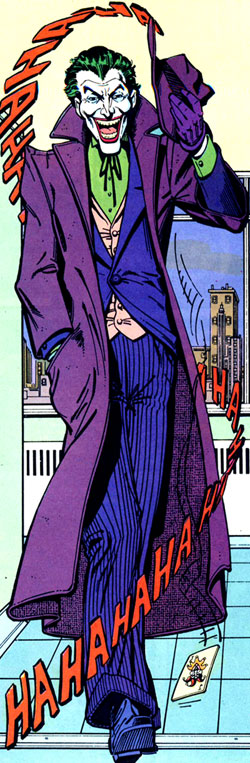

From the start, he’s an amazing visual, and it’s a complete inversion of the classic hero and villain formula. Batman was inspired as much by Count Dracula and the Shadow as he was heroes like Zorro, with a costume designed to frighten, but he’s still the good guy. The one in the bright colors with the big smile who does magic tricks… that’s the one you need to watch out for.

By the Silver Age, though, things have changed, largely due to the tonal shift that resulted from the Comics Code, and without the edge of madness and outright shrieks of “I’m going to kill you,” the Joker loses a lot of his villainous mojo and fades back to be just another visually interesting face in the crowd.

For evidence, you don’t need to look any further than the 1966 TV show. For all the fan grousing about how its campiness detracted from the legitimate storytelling of the comics–and the eye-rolling that goes with the fact that it’s been forty-two years and we still can’t get a headline about comics without “Biff! Pow!” or “Holy Lazy Copywriters, Batman!”–anyone who’s actually ever read Silver Age Batman stories can tell you that the show reflected the goofiness of the comics, not the other way around.

can tell you that the show reflected the goofiness of the comics, not the other way around.

In any case, as entertaining as Cesar Romero’s Joker is–and brother, he is entertaining–he’s just another thematic villain for Batman to deal with that week. Swap out the playing cards and clown puns for birds, Egyptian artifacts, dinosaur eggs or cat statues, and the stories could’ve been about anybody in the cast. There’s not a whole lot that’s distinctive about him–when you stack him up against the rest of the arch-criminals, anyway–and aside from the visual aspects, there’s almost nothing in the character that we’d recognize as the Joker of today.

There is, however, a lot that we’d recognize as today’s Joker on the show itself, it just doesn’t come from the Joker; it comes from the Riddler.

It all comes down to Frank Gorshin, who just played the hell out of the role, snapping back and forth from manic glee to genuinely chilling obsession several times in every scene at a pace that would mirror the Joker’s portrayal in Batman: The Animated Series–which also reinvented the Riddler as a far more smug, intellectual villain–twenty-five years later.

But as for the Joker, well… Cesar Romero’s great and I wouldn’t trade his Joker for the world, but there’s a reason the series led with the guy in green.

By the mid-80s, though, everything had changed again. Instead of the guy who carried out clown-themed robberies and pulled boners, there was a character that was firmly entrenched as Batman’s arch-enemy. This was the Joker in full end-boss mode, the Final Form of the Clown Prince of Crime that shot and paralyzed Barbara Gordon and gleefully beat Robin to death with a crowbar

and gleefully beat Robin to death with a crowbar . This is the guy who pushes Batman to his limit in Dark Knight Returns

. This is the guy who pushes Batman to his limit in Dark Knight Returns and snaps his own neck after a triple-digit murder spree, just to make everyone think Batman’s finally lost it. This, my friends… this is an arch-nemesis.

and snaps his own neck after a triple-digit murder spree, just to make everyone think Batman’s finally lost it. This, my friends… this is an arch-nemesis.

But those aren’t what make him the go-to bad guy; the Joker’s a part of all those stories because he’s already Batman’s arch-enemy. Even in the finale of Batman Year One –the Alpha to DKR‘s Omega–the Joker’s used as shorthand for the new type of criminal that’s going to be rising to challenge Batman. He’s the escalation, the one that can’t be intimidated by Batman’s physicality or figured out by his deductions or scared by his demonic costume. The scene works not just because we know what the Joker card means when Gordon hands it to Batman, but because we know that the Joker is the one you have to worry about.

–the Alpha to DKR‘s Omega–the Joker’s used as shorthand for the new type of criminal that’s going to be rising to challenge Batman. He’s the escalation, the one that can’t be intimidated by Batman’s physicality or figured out by his deductions or scared by his demonic costume. The scene works not just because we know what the Joker card means when Gordon hands it to Batman, but because we know that the Joker is the one you have to worry about.

Clearly, this is the “real” Joker and not the watered down version, which leads to the question of what changed? Was it just a slow build that returned the Joker to his roots, a combination of his lasting visual appeal and the further refining of Batman as the ultra-competent super-detective adventurer that he evolved into? Maybe, but I’m of the opinion that there has to be a turning point somewhere.

After all, most of the great villains of comics have the moment where you know that Everything Changes. Dr. Doom, for instance, starts out as a visually interesting character with an awesome name, but until he steals the Power Cosmic and becomes DOCTOR DOOM, he’s just a cool-looking guy that once sent the Fantastic Four back in time to look for pirate treasure. The Green Goblin was a legitimate threat with an interesting hook and some good stories under his belt, but he wasn’t the Spider-Man villain until he chucked Peter Parker’s girlfriend off a bridge. Even Lex Luthor, who was an ever-present arch-nemesis for Superman, didn’t really reach his full potential until we saw how far he was willing to damn himself for revenge in–of all things–an imaginary story .

.

With the Joker, it’s a little harder to pin down. Like Luthor, he’s almost omnipresent, the strength of the earlier stories, the visual contrast and the prominence of his character on the TV show pushing him to the forefront for most of the character’s life. But given the timeframe we’re working with, I’d have to say that it really comes down to two stories from the ’70s that put him over the top.

The first, of course, is the Denny O’Neil/Neal Adams classic “The Joker’s Five-Way Revenge “, from 1973’s Batman #251.

“, from 1973’s Batman #251.

To be honest, this one almost gets a pass solely based on it being one of the most beautiful things Neal Adams ever drew, but at its heart, it’s more of an archetypal story of Batman than the Joker.

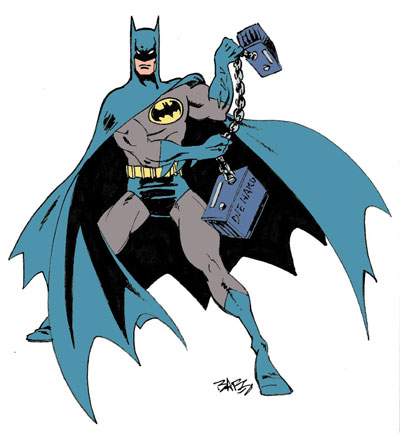

It does, after all, have pretty much everything you want to see from Batman: The casual way he takes a thug’s veiled punches and then lays him out in one shot (a trademark of O’Neil’s ’70s Batman), the deduction of where the Joker’s hiding based off the dirt on his shoes, he fights a shark, and of course… well, just look at this thing:

Absolutely gorgeous.

Of course, it is a Joker story, and O’Neil did a lot to bring back what was so compelling about the character: He’s on a murder spree that’s ostensibly based on getting revenge against the henchman who sold him out, but beneath the surface, there’s the idea that for the Joker, it’s far easier to just kill five people than find out which one ratted him out. Add to that the fact that he’s around thirty real-time years into his criminal career at this point and would therefore probably be heading off to jail anyway with or without the evidence of his ex-flunkie, and you’ve got someone who breezes into town like a thunderstorm and just starts killing because it’s second nature to him.

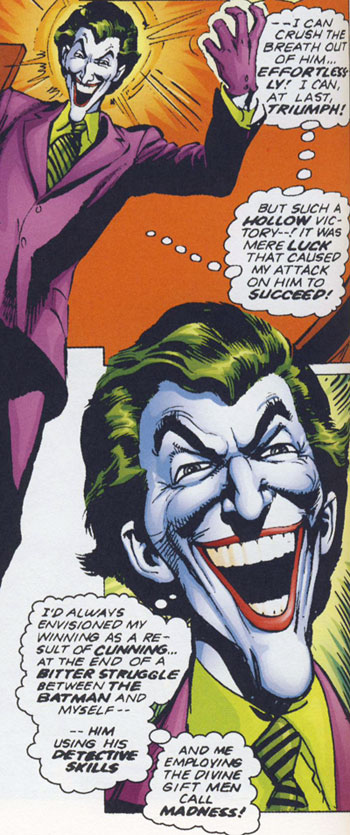

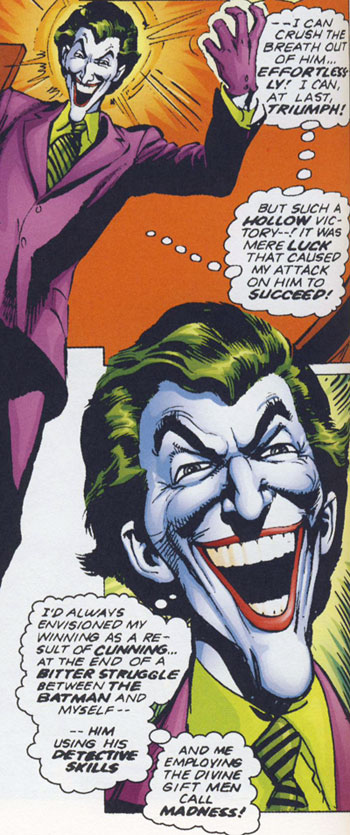

Also, O’Neil brings in one of the most important and lasting aspects of the character–His “game” against Batman:

There are a few more villains who’d rather beat Batman than kill him–the Riddler springs to mind–but by refusing to kill him when the opportunity presents itself, as it does more than a couple of times, the Joker sets himself up as Batman’s equal and adds an even more sinister aspect to his crimes. The people he murders are less than nothing to him; it’s not about them. It’s not even about himself, it’s just about baiting Batman into another confrontation.

The one that really defines the Joker, though, is the Steve Englehart and Marshall Rogers’ The Laughing Fish/Sign of the Joker from 1978’s Detective #475-476, which gives us the amazing, iconic image at the top of this post.

from 1978’s Detective #475-476, which gives us the amazing, iconic image at the top of this post.

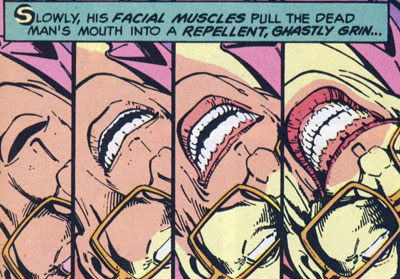

Englehart’s entire run on Batman is a nod to the Golden Age, bringing back what were then all-but-forgotten characters like Hugo Strange and Deadshot and reinventing them to fight a more streamlined Batman. For the Joker, though–the story that finished out his run on the title–Englehart went back to the character’s origin story and retold it with the addition of the “Jokerized” fish–infected with the “Joker Venom” that had been his weapon of choice in 1940 and returned in “Five Way Revenge,” brought directly into focus by Rogers:

It’s a strange addition, but it’s one that changes the tone of the story completely. In 1940’s “The Joker,” the murders are all organized around robberies, but for “The Laughing Fish,” the Joker’s motivation–killing government employees because he can’t copyright the fish he’s infected–is completely insane. It’s a premise so silly that it could be a Daffy Duck plot if it didn’t end with the Joker murdering at will while Batman and the entire Gotham City police force watched helplessly.

It’s also worth noting that Marshall Rogers didn’t just draw the Joker as a man who smiled all the time, but as a man who couldn’t do anything but smile, an influence that he traced back to the 1928 film The Man Who Laughs, which lent its title to another retelling of the first Joker story by Ed Brubaker and Doug Mahnke . This, according to Rogers, was the central tragedy of the Joker: Even if he wanted to cry at all the horror he had caused, he was physically incapable of doing anything but laughing at it, a theme that continued into The Killing Joke.

. This, according to Rogers, was the central tragedy of the Joker: Even if he wanted to cry at all the horror he had caused, he was physically incapable of doing anything but laughing at it, a theme that continued into The Killing Joke.

More importantly, though, this is the story that brings the one great similarity between Batman and the Joker to the forefront: They’re both amazing planners. I mentioned before that the Joker’s the embodiment of chaos, but in this story–and others, including The Dark Knight–the way he spreads anarchy is through meticulous plans and an ability to second-guess and out-think everyone at any turn. When Batman disguises himself as the second victim, the Joker poisons the man’s cat, knowing that it’ll find its master by scent. He already knows the best-laid plans, and like entropy itself, he’s always one step ahead of them.

Incidentally, on the animated series, they added aspects of “Five Way Revenge” to the episode based on “The Laughing Fish” to meet the standard of shark-fighting.

For my money, though, it all comes down to the Laughing Fish. The way it draws on the Golden Age story to bridge the gap to the Modern Age, the element of mad randomness and anarchy that’s built on meticulous planning, the fixed grin. It’s as close to a turning point for the character as you’re likely to find.

Of course, three years prior to the story, the Joker was already popular and prominent enough to carry his own solo series, even if it did last a short nine issues, so who knows?

, signed by me, and…