So earlier tonight, Dr. K pointed me to an article at the Comics Reporter where The Spurge thoughtfully listed fifty things that, according to him, every comics collection needs to be complete. And while I hate to be the guy to come in and say I can do better (this is a lie, I love being that guy), I’m pretty sure I can do better.

And I can do it in half the time.

I mean, sure. You could sink your money into the complete works of Chris Ware and the dead-eyed horror of Little Orphan Annie, but what’ll that get you? Anyone can make a comics collection complete.

Making it completely awesome, however, requires a bit of help, which is why I’m sweeping in for tips on how you can tailor your collection for maximum radness and a lucrative career posting scans of kooky ’60s comics with funny captions.

Keep in mind, this list assumes that you’ve already covered the basics

basics , and are looking to trick it out. Allow me, then, to be your personal Xzibit.

, and are looking to trick it out. Allow me, then, to be your personal Xzibit.

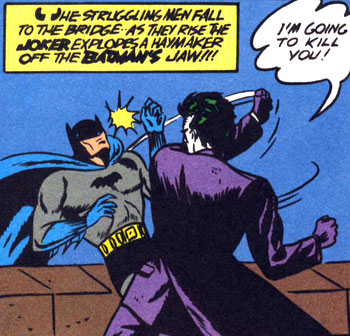

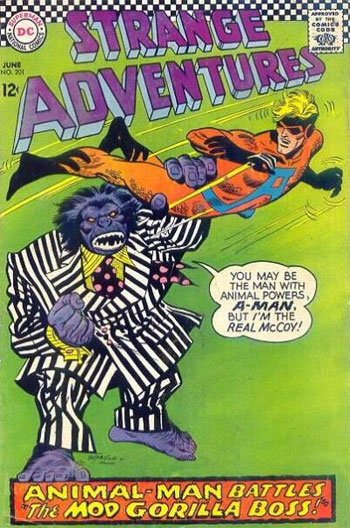

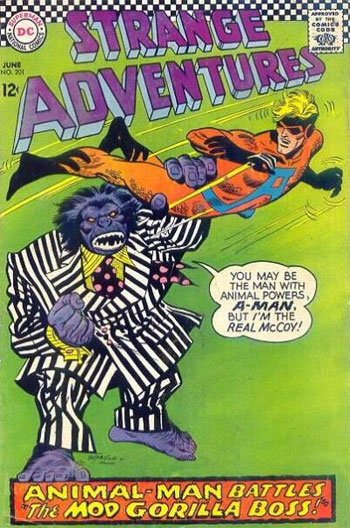

1. The Mod Gorilla Boss

Or, failing that, the Primate Patrol, Francois the Nazi-Fighting Gorilla, Super-Gorilla Grodd or a number of others. Why? Because it’s important to understand the relationship that comics have had with gorillas and monkeys over the years. I mean, think about it: Imagine if you will a world where Every Which Way But Loose, in which Clint Eastwood stars as a trucker who fights for money and has a pet orangutan, was so influential on the world of filmmaking that Hollywood had tried every year to top it. That’s what comics are like, to the point where the Flash not only fights a gorilla, but a talking telepathic cannibal super-gorilla, and we don’t even bat an eye.

2. A Collection Of Stories From The Golden Age

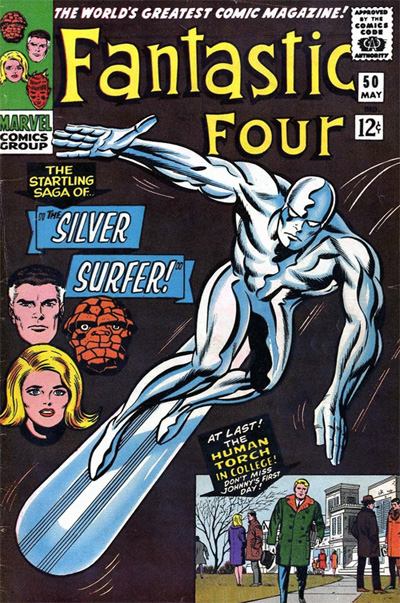

Every now and then, I’ll wonder what it was like to be there at one of the moments when Everything Changed, like being there to pick Fantastic Four #1 up off the rack and seeing how different it was from anything else I’d ever seen. But the fact of the matter is that I’d rather be reading comics now than at any time in history, because there’s such a wealth of reprints going around.

Every now and then, I’ll wonder what it was like to be there at one of the moments when Everything Changed, like being there to pick Fantastic Four #1 up off the rack and seeing how different it was from anything else I’d ever seen. But the fact of the matter is that I’d rather be reading comics now than at any time in history, because there’s such a wealth of reprints going around.

Not just in terms of cheap reprint books like DC’s Showcases and Marvel’s Essentials–although those are worth their weight in gold to the amateur retrologist–but in that over the past decade, there’s been a concerted effort to shine a light on the forgotten treasures of the Golden Age. Even Marvel, which has–for good reason–long ignored its Timely roots in favor of Stan and Jack’s 1961 starting point, have gotten into the act with collections of Daring Mystery and USA Comics

and USA Comics dropping in the past year.

dropping in the past year.

And you need to read them, because they are fucking insane.

The two titles mentioned above include both a hero from an underground nation that is exactly the size of the United States of America who fights Nazi saboteurs and elves in equal measure and a Hobo Super-Hero named the Vagabond who is not actually a hobo (he’s a hobo clown who is actually an FBI agent) and is not actually called the Vagabond (he is “better known to himself as Chauncey Throttlebottom III”). These are the punk rock of comics. They’re the ones that a bunch of kids were making back when the rules hadn’t even been invented yet, when comics were a blank slate with no idea that was too crazy, nonsensical or downright unreadable to get published.

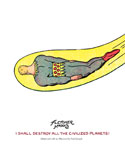

If you only get one, though, it should be Paul Karasik’s collection of Fletcher Hanks stories, I Shall Destroy All The Civilized Planets , which is just jaw-droppingly surreal. Seriously.

, which is just jaw-droppingly surreal. Seriously.

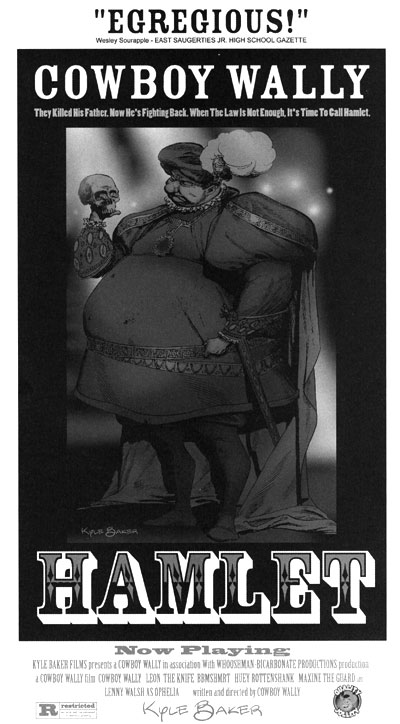

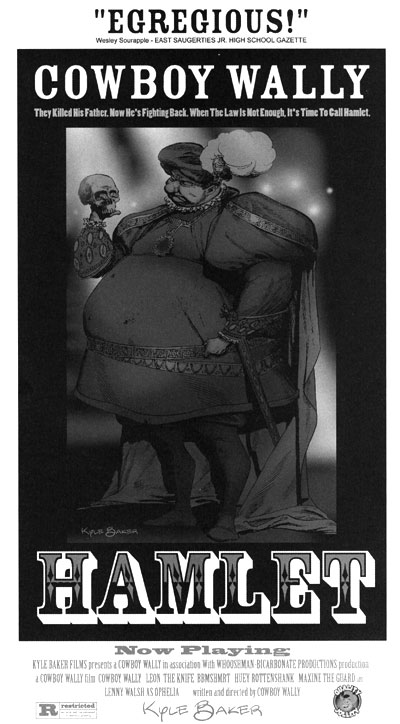

3. At Least One Comic By Kyle Baker

Because no one–no one–should live a life without Cowboy Wally .

.

4. A Prose Novel About Comics

And no, Greg Rucka’s novelization of No Man’s Land doesn’t count, no matter how entertaining it actually is. Now, the obvious choice here would be Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay , the story of two young men at the dawn of the Golden Age, as it won a little thing called The Pulitzer Prize, and therefore gave Chabon the right to refer to any and all Eisner winners as “quaint.” And it’s good, too, and well worth picking up. But, there’s another book that’s far less well-known that fits the bill: Robert Mayer’s Superfolks

, the story of two young men at the dawn of the Golden Age, as it won a little thing called The Pulitzer Prize, and therefore gave Chabon the right to refer to any and all Eisner winners as “quaint.” And it’s good, too, and well worth picking up. But, there’s another book that’s far less well-known that fits the bill: Robert Mayer’s Superfolks , a groundbreaking, darkly comedic story of the human side of a retired super-hero that hit shelves in 1977 and quietly influenced creators like Alan Moore, Kurt Busiek and Grant Morrison, even prompting the latter two to write forewords for its last two editions. I’m always a little amazed that it’s not brought up more often, but it’s there, it’s amazing, and having it on your shelf will serve as a subtle reminder that you occasionally read books without pictures in them.

, a groundbreaking, darkly comedic story of the human side of a retired super-hero that hit shelves in 1977 and quietly influenced creators like Alan Moore, Kurt Busiek and Grant Morrison, even prompting the latter two to write forewords for its last two editions. I’m always a little amazed that it’s not brought up more often, but it’s there, it’s amazing, and having it on your shelf will serve as a subtle reminder that you occasionally read books without pictures in them.

5. Something That Will Allow You To Sound Smart In Public

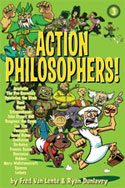

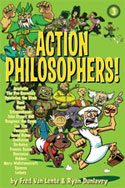

I refer, of course, to Fred Van Lente and Ryan Dunlavey’s Action Philosophers!, a comic that I’ve said time and again should be in every library in the world.

I refer, of course, to Fred Van Lente and Ryan Dunlavey’s Action Philosophers!, a comic that I’ve said time and again should be in every library in the world.

I’ll be honest with you, folks: I took one (1) course in Philosophy in college, and while I’m normally a pretty good student (shocking, I know), I did miserably. The best thing to come out of it was a note on my paper from my prof that read “You write so well that it’s a shame you have no idea what you’re talking about.” Seriously.

Since the debut of AP, however, I find myself not only interested in the subject, but versed enough in the details to discuss the finer points of Lao Tzu and Spinoza with other people, although I’ll confess that these conversations usually occur over drinks and involve me struggling to remember that Wittgenstein didn’t actually have Angry Lines radiating from his head at all times.

6. A Comic That, If It Came To It, Could Block Shuriken, Blowdarts, And Most Medium Caliber Handgun Rounds

Or: “A Slipcased Hardcover So Expensive That You Hope For The Inevitable Zombie Uprising That Will Force You To Use It As A Club, Thereby Justifying the Amazing Expense.” I’m looking at you here, Completely MAD Don Martin .

.

7. One, and Only One, Issue of Pizzazz

Specifically, this one:

8. A Comic Written by a Rapper

This is becoming an increasingly easy one to find, with the Method Man’s graphic novel out recently and one from the GZA in last month’s Previews catalog, and if you’re out for something more revolutionary, you could track down last year’s sadly unfinished Public Enemy (cowritten by Chuck D), wherein–and I am not making this up–Flava Flav uses a clock on a chain to battle evil government thugs.

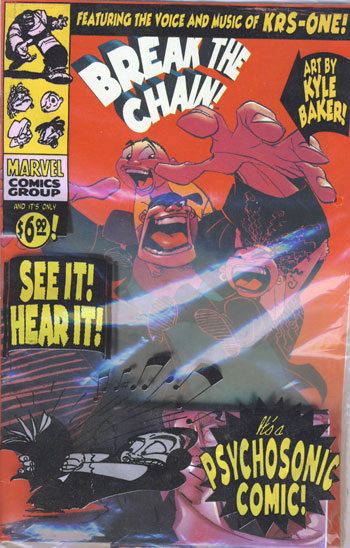

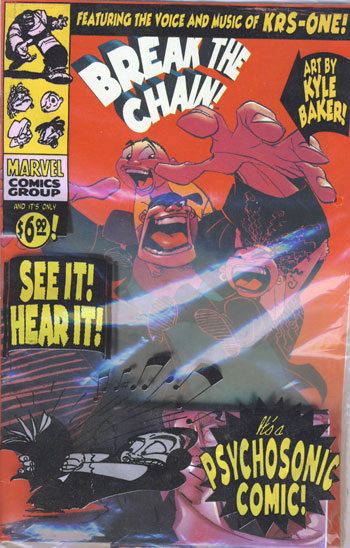

If you’re really dedicated though, and you want to kick it Old School, you can attempt to track down this bad boy:

That’s right: 1994’s Break The Chain by Kyle Baker and KRS-One, which originally came polybagged with a casette tape of the Blastmaster rapping the script with instructions to turn the page every time he says “Word!” I have had this thing sitting on the shelf for two years without even opening it. I don’t think my house could contain that much awesome.

9. Jack Staff

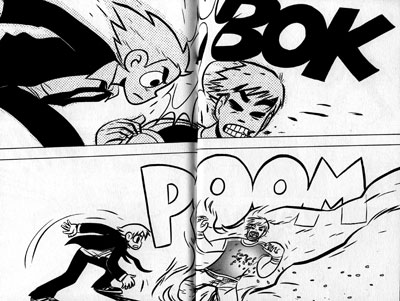

I’ve mentioned before that while I’m usually a little reticent to call something my favorite comic–because let’s face it, I fall in love with something new at least once a week–there’s no question in my mind that Paul Grist’s Jack Staff

I’ve mentioned before that while I’m usually a little reticent to call something my favorite comic–because let’s face it, I fall in love with something new at least once a week–there’s no question in my mind that Paul Grist’s Jack Staff takes the cake. And it’s something everyone oughtta have, not just because it’s an amazingly fun read that’s still one of the most engaging and innovative comics I’ve ever read, but because it teaches us a valuable lesson.

takes the cake. And it’s something everyone oughtta have, not just because it’s an amazingly fun read that’s still one of the most engaging and innovative comics I’ve ever read, but because it teaches us a valuable lesson.

Jack Staff started out as a rejected Marvel pitch. That explains, of course, why Jack himself bears a strong resemblance to Marvel’s vampire-hunting Union Jack, and why–especially in the first story–there are analogues for other characters cropping up: Sgt. States in lieu of Captain America, Tom Tom the Robot Man filling in for Iron Man and so on. But beyond that is the fact that Marvel rejected what would eventually grow and evolve into the best comic I read. There’s a lesson about perseverance in there, and like all the best morals, it comes wrapped in the story of Becky Burdock, Vampire Reporter.

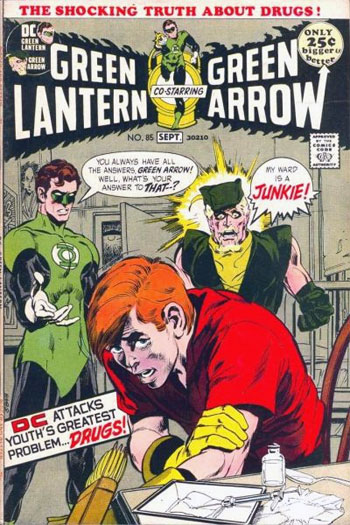

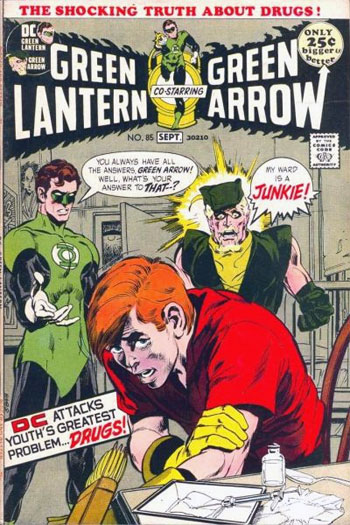

10. A Story That Deals With a Serious Issue

Because it’s important to know that there was a time when stories like the one above were saying things that nobody else did, and that no matter how hokey and cliché they might seem now, there was a time when they were as earnest and unflinching as they’d eventually become.

Unless you’re Judd Winick, in which case they’re simultaneously earnest and unbearably hokey.

11. Something Romantic

Because every now and then, a young man or woman’s fancy turns to ahhhhhhrrrrromance! But don’t feel that you have to go with Blankets or Spider-Man Loves Mary Jane or the dismal, heartsick pit that is the Charlton Romance Comic! There are lots of things in comics that are romantic!

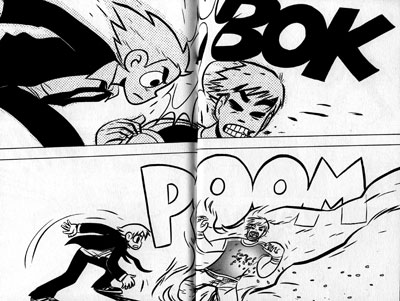

Like the time Scott Pilgrim headbutted that guy so hard he turned into change!

Now that is the glory of love.

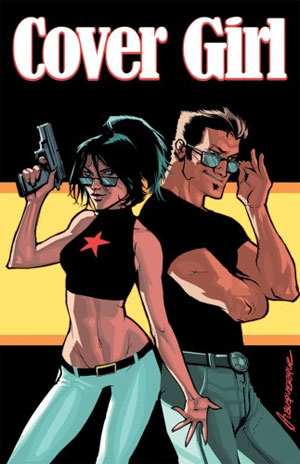

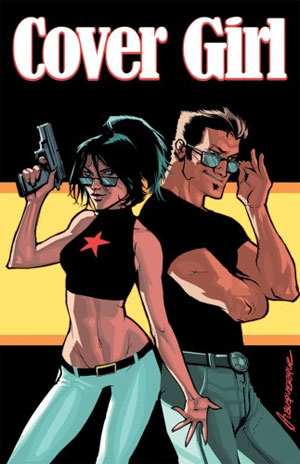

12. Cover Girl, by Andrew Cosby, Kevin Church and Mateus Santolouco

This Entry Sponsored By BeaucoupKevin.com

13. Something That Is Totally Awesome But That You Totally Do Not Understand

I find that most great manga and the works of Bobs Haney and Kanigher fit into this category pretty nicely.

14. Something That You Can Give To Someone Who Doesn’t Get It

For any dedicated comics reader, there’s always that moment where you go up against a friend, significant other or family member who wants to understand your love of comics, but meets you with a blank stare no matter how many times you try to explain the whole Every Which Way But Loose metaphor.

The problem here is that in order to capture your love for comics, they need to have that one defining moment, and since that’s a lot more likely to come along when one is six years old at the Ameristop looking for something to kill time between cartoons, you’re usually too late, and have to come up with something that’s both an entry-level book and embodies everything you love about comics. It’s a tough one, since every person’s tastes are going to be different, but as a good place to start, you could do a lot than Scott McCloud’s Zot! , though depending on your affection for River City Ransom, Scott Pilgrim does a heck of a job.

, though depending on your affection for River City Ransom, Scott Pilgrim does a heck of a job.

15. A Comic That Was Ten Years Ahead of Its Time

In the forties, it was Jack Cole’s Plastic Man and Will Eisner’s Spirit. In the fifties, it was the EC Books. In the sixties, Metamorpho and Herbie

and Herbie , and in the ’90s it was Starman

, and in the ’90s it was Starman . Every good comic is going to stick out from the crowd, but these and others are the ones that read like they were sent back from the future to show people how it was going to be done, whether it’s in panel layout or self-aware humor or kicking off the trend of retrospective super-hero comics that continues today. They’re the leaps forward in the form. They are, in effect, the mutants of comics.

. Every good comic is going to stick out from the crowd, but these and others are the ones that read like they were sent back from the future to show people how it was going to be done, whether it’s in panel layout or self-aware humor or kicking off the trend of retrospective super-hero comics that continues today. They’re the leaps forward in the form. They are, in effect, the mutants of comics.

And comics love mutants.

16. Porn

Yeah, that’s right. I said it.

I’ve mentioned it before, the marriage of comic books and pornography is often one that falls extremely flat, as any harrowing look through the pages of Previews Adult will show. I’m not sure if it’s just a side effect of sixty years of engaging in adolescent power fantasies rather than just adolescent fantasies, but it’s rare that anything comes along that’s worth bothering with.

I’ve mentioned it before, the marriage of comic books and pornography is often one that falls extremely flat, as any harrowing look through the pages of Previews Adult will show. I’m not sure if it’s just a side effect of sixty years of engaging in adolescent power fantasies rather than just adolescent fantasies, but it’s rare that anything comes along that’s worth bothering with.

Which is why it’s always interesting when something does. There’s Alan Moore’s Lost Girls–which is not to be confused with Alan Moore’s The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: The Black Dossier, which is only porn for research librarians–and Phil Foglio’s long-running XXXenophile, in which centaurs factor and it’s actually pretty funny. Even so,it’s Colleen Coover’s Small Favors that I like the most, probably owing to the fact that it can honestly be described as “cute and hilarious” and has a premise so strange that it could’ve come from Bob Haney, in that the principal characters are a girl and the size-changing manifestation of her conscience that was assigned to her by an old woman who lives in the girl’s head to keep her from doing exactly what they end up doing.

And on the flipside…

17. Something For The Kids

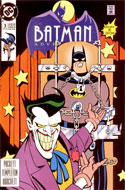

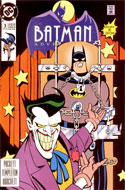

So here’s the deal: Back before DC decided that there was no middle ground between Identity Crisis and DC Super Friends, there was a long stretch of time in which both the best Batman comic and the best Superman comic by far were the kid-friendly, done-in-one issues that tied into the animated series. Kelley Puckett and Mike Parobeck’s Batman Adventures

So here’s the deal: Back before DC decided that there was no middle ground between Identity Crisis and DC Super Friends, there was a long stretch of time in which both the best Batman comic and the best Superman comic by far were the kid-friendly, done-in-one issues that tied into the animated series. Kelley Puckett and Mike Parobeck’s Batman Adventures were like textbook examples of how to tell great Batman stories, and Mark Millar’s work on Superman Adventures

were like textbook examples of how to tell great Batman stories, and Mark Millar’s work on Superman Adventures are not only the best Superman comics of the ’90s, but the best work of the man’s career. They’re that good.

are not only the best Superman comics of the ’90s, but the best work of the man’s career. They’re that good.

And yet they never really sold all that well, a bit of history that’s repeating itself today, when Marvel Adventures Avengers is the best Avengers book in quality and the worst in sales. Why? Because it’s a kid’s book. And even stranger, I’ve had customers that come in asking for new Shazam stories that turn their nose up at Mike Kunkel’s Billy Batson and the Magic of Shazam because they want serious stories.

About Captain Marvel.

Who is a child who turns into a super-powered grown-up when he says a magic word.

AND FIGHTS A WORM WITH A RADIO ON ITS NECK.

Brother, I don’t even know where to begin with the logic behind that, but I’ll try to sum it up like this: There are good stories for mature readers that couldn’t have been done otherwise (see above), but a good story is good no matter what age group it’s directed at, and to paraphrase Penny Arcade, if you’re worried that somebody’s going to think you’re immature for reading a kid’s comic, then guess what? You’re already reading comics, and they’re not going to care if it comes from Vertigo or Johnny DC. Sheesh.

And speaking of Penny Arcade…

18. A Print Collection of a Webcomic

At this point, I think it’s become obvious that–just as it was with music–the Internet is the unavoidable future of comics, both in terms of distribution (everyone’s enjoying those discounts on trades at Amazon, right?) and creation, largely through the medium of webcomics. Still, there’s always going to be a market for print and at least for now, one of its chief benefits is a sense of legitimacy that comes with a hard copy.

I mean, let’s be honest here: Webcomics–like blogs–are relatively cheap and easy to create, to the point where anyone can do it, but getting a book published is a heck of a lot harder than setting up a website. The end result to all this: the ones that do get picked up tend to offer a lot more once they do, whether it’s additional strips like Order of the Stick, bonus commentary like Penny Arcade , or beautiful formats like Achewood

, or beautiful formats like Achewood and Wondermark

and Wondermark , and that’s in addition to being able to read through them in the rare event that you’re away from your computer.

, and that’s in addition to being able to read through them in the rare event that you’re away from your computer.

Plus, you know you want to have this in your house:

19. A Story That Hits All Three

My friend Scott has a theory about what makes a good comic that goes like this: There are three types of ways that a comic can affect you. It can go to your head and make you think, your heart for an emotional connection, or your gut for the fist-pumping “fuck yeah!” moment. Anything that gets one is enjoyable, and a good comic will get you two, but a great comic… That’s one that hits all three.

Like, say, JLA #41, when they’re fighting Mageddon the Anti-Sun and the Justice League gives everyone on the planet super-powers and they all fly out to space to help Superman. Not only is that a clever solution that works within the context of the story and makes perfect sense given that it takes place in a world where everyone on the planet owes Superman their life a hundred tiems over, but it’s such a great image. Everybody in the world getting superpowers! And… and they put aside all their differences to help Superman… and..

Sorry, got a little something in my eye. I’ll meet you down at #20.

20. A Run You Had To Hunt For

I mentioned before that one of the reasons I love reading comics right now is that there’s so much stuff that’s available, and that’s true. And yet, there are still comics that have never been reprinted.

Two of the best comics DC’s ever published are Suicide Squad and Hitman, and if you want ’em in trade, you’re out of luck. Yes, they did publish a few trades for Hitman while the series was coming out, but they never got to the later issues, and I’m pretty sure that the only issue of Suicide Squad that’s ever seen a reprint is #13, which shows up in the Justice League International

Two of the best comics DC’s ever published are Suicide Squad and Hitman, and if you want ’em in trade, you’re out of luck. Yes, they did publish a few trades for Hitman while the series was coming out, but they never got to the later issues, and I’m pretty sure that the only issue of Suicide Squad that’s ever seen a reprint is #13, which shows up in the Justice League International hardcover.

hardcover.

Now, if those two series–or ROM, for that matter–were collected tomorrow you could sit down, read ’em, and have a fantastic time. But there’s something about having to hunt down an issue to complete a run that’s an entirely different experience, and while I want trades of those issues as much as anyone, the thrill of triumph is something that everybody ought to feel.

Ditto for the disappointment when you get that last handful of Dr. Fate and find out that your friends like it a heck of a lot more than you do.

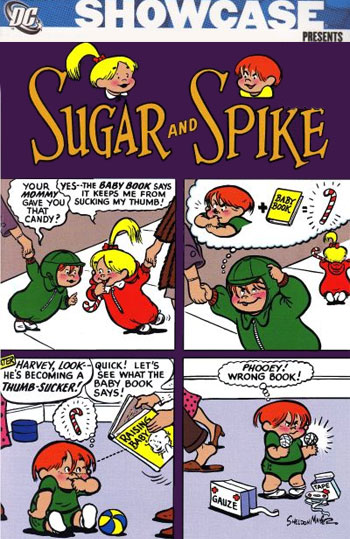

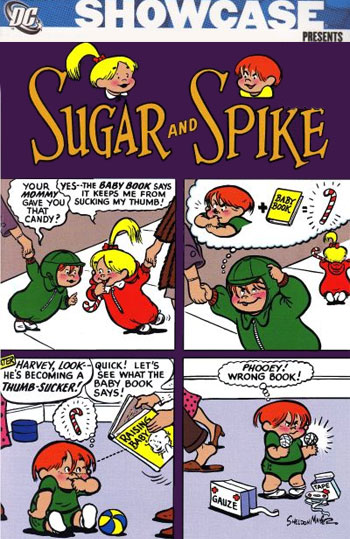

21. Showcase Presents Sugar & Spike

OH WAIT! I FORGOT! THIS DOES NOT EXIST BECAUSE DC HATES MONEY.

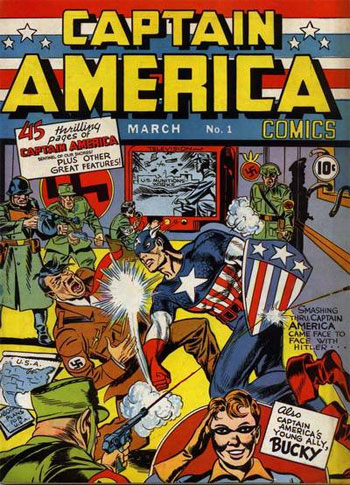

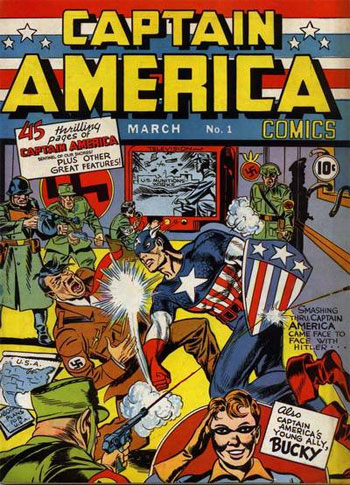

22. A Comic Where Somebody Punches Hitler

Because seriously, fuck that guy.

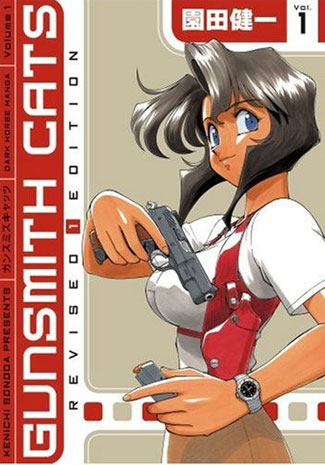

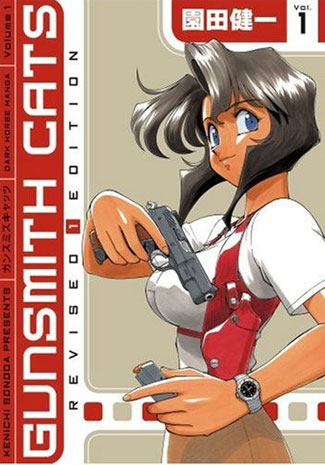

23. Something That You Absolutely Love, Except For One Little Thing

“Oh man, this thing is great! A couple of sexy girl bounty hunters blowing stuff up and getting in car chases in Chicago! And the art’s beautiful! The cars and guns are painstakingly researched, and the car chases have a sense of motion to them that I’ve never seen before in comics! The jokes are funny and the action’s intense and… Hey, wait. It says that Ken and Minnie May were shacking up together ‘four years ago.’ But… but she’s eighteen now… and he’s in his thirties.

is great! A couple of sexy girl bounty hunters blowing stuff up and getting in car chases in Chicago! And the art’s beautiful! The cars and guns are painstakingly researched, and the car chases have a sense of motion to them that I’ve never seen before in comics! The jokes are funny and the action’s intense and… Hey, wait. It says that Ken and Minnie May were shacking up together ‘four years ago.’ But… but she’s eighteen now… and he’s in his thirties.

…

Ooh, a Bean Bandit story!”

24. Something That Might Not Be Very Good But God Damn It, It Means The World To You

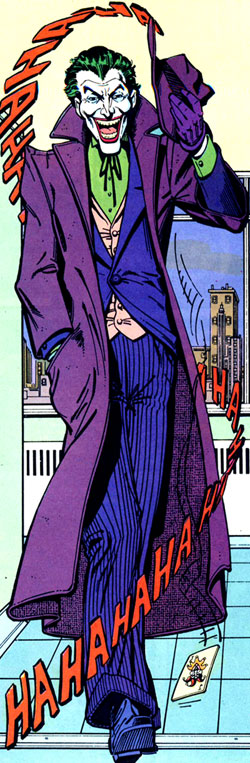

25. Something That You Absolutely Hate

Why? Because if you’re gonna read comics for any serious amount of time, you can’t read the good stuff all the time. Now, I would never advise someone to keep reading a book they didn’t like; if you stop enjoying a comic, then stop reading it. But… if you find something so monumentally bad that it transcends itself into something beyond, something that you can’t believe could possibly exist in a world that also has Watchmen in it, then you’ve got to stick with that one, whether you’re gleefully marveling at it or just trudging through for the benefit of others

Mithridates, after all, died old.

Every now and then, I’ll wonder what it was like to be there at one of the moments when Everything Changed, like being there to pick Fantastic Four #1 up off the rack and seeing how different it was from anything else I’d ever seen. But the fact of the matter is that I’d rather be reading comics now than at any time in history, because there’s such a wealth of reprints going around.

Every now and then, I’ll wonder what it was like to be there at one of the moments when Everything Changed, like being there to pick Fantastic Four #1 up off the rack and seeing how different it was from anything else I’d ever seen. But the fact of the matter is that I’d rather be reading comics now than at any time in history, because there’s such a wealth of reprints going around.

I refer, of course, to Fred Van Lente and Ryan Dunlavey’s Action Philosophers!, a comic that I’ve said time and again should be in every library in the world.

I refer, of course, to Fred Van Lente and Ryan Dunlavey’s Action Philosophers!, a comic that I’ve said time and again should be in every library in the world.

I’ve mentioned before that while I’m usually a little reticent to call something my favorite comic–because let’s face it, I fall in love with something new at least once a week–there’s no question in my mind that Paul Grist’s

I’ve mentioned before that while I’m usually a little reticent to call something my favorite comic–because let’s face it, I fall in love with something new at least once a week–there’s no question in my mind that Paul Grist’s

I’ve

I’ve  So here’s the deal: Back before DC decided that there was no middle ground between Identity Crisis and DC Super Friends, there was a long stretch of time in which both the best Batman comic and the best Superman comic by far were the kid-friendly, done-in-one issues that tied into the animated series. Kelley Puckett and Mike Parobeck’s

So here’s the deal: Back before DC decided that there was no middle ground between Identity Crisis and DC Super Friends, there was a long stretch of time in which both the best Batman comic and the best Superman comic by far were the kid-friendly, done-in-one issues that tied into the animated series. Kelley Puckett and Mike Parobeck’s

Two of the best comics DC’s ever published are Suicide Squad and Hitman, and if you want ’em in trade, you’re out of luck. Yes, they did publish a few trades for Hitman while the series was coming out, but they never got to the later issues, and I’m pretty sure that the only issue of Suicide Squad that’s ever seen a reprint is #13, which shows up in the

Two of the best comics DC’s ever published are Suicide Squad and Hitman, and if you want ’em in trade, you’re out of luck. Yes, they did publish a few trades for Hitman while the series was coming out, but they never got to the later issues, and I’m pretty sure that the only issue of Suicide Squad that’s ever seen a reprint is #13, which shows up in the